As well as entertaining us, the film industry and Hollywood have given us some wonderful quotes that have entered into our everyday language.

From, “Frankly Scarlett, I don’t give a don’t give a damn,” or “You’re only supposed to blow the bloody doors off,” to the menacing, “I’ll be back,” we love the snazzy soundbite, but maybe the best of them all hit our screens in 1986 with the testosterone-fuelled hit, Top Gun. As they walk towards their F-14 fighter jets, Tom Cruise and Anthony Edwards, AKA Maverick and Goose, share high fives with the iconic: “I feel the need, the need for speed!”

Well, with just one tiny change, their saying becomes “the Greed for Speed”, which is a clever description for one of the core fundamental changes that has swept through our sport. Of course, with dinghy racing being a competitive sport, there has always been a demand for more power and speed as getting to the finish line faster than the rest is what it is all about; so in some ways, the Greed for Speed is nothing new.

For UK dinghies, we can probably identify one of the first, if not the first example of a boat that was designed specifically with speed in mind with the BRA 1. A while earlier, the BRA (Boat Racing Association) had splintered off from the mainstream of yachting when it was thought that small boat and dinghy sailing was not being properly represented, and one of their first projects was a design competition for a 12ft racing dinghy that had boatspeed as one of the core criteria.

The winning boat in the competition, George Cockshott’s BRA 1, showed a move towards many of the features that have since then become synonymous with increased performance, with a lighter weight, flatter underwater sections and a straighter run aft towards a beamier transom.

In time the BRA 1 would be re-badged as the International 12, but it would be in its bigger sister, the International 14, that the Greed for Speed would take on a new importance. Within the confines of what would become known as ‘restricted development’, such was the pace of change (much of it driven by developments from Uffa Fox on the Isle of Wight) that the ‘new boat a year’ mentality would soon be accepted as the norm.

Although the 12 and 14ft dinghies were both called ‘International’, with regular competition starting to take place between nations (something that the International Canoes had been good at for many a year), it would not be until the post-war years that dinghy sailing would really go ‘global’. When it did, with the world being shrunk by better communications and easier travel, there would be a whole new set of influences suddenly starting to redirect the focus of dinghy development.

The Greed for Speed was about to get turbo-charged when, in the early 1950s, the IYRU (now World Sailing) introduced the term ‘performance sailing’ into our language. At the heart of their thinking was the realisation that in various centres of sailing around the world, innovative sailors were finding ways to bring a step function into the speed of sailing dinghies.

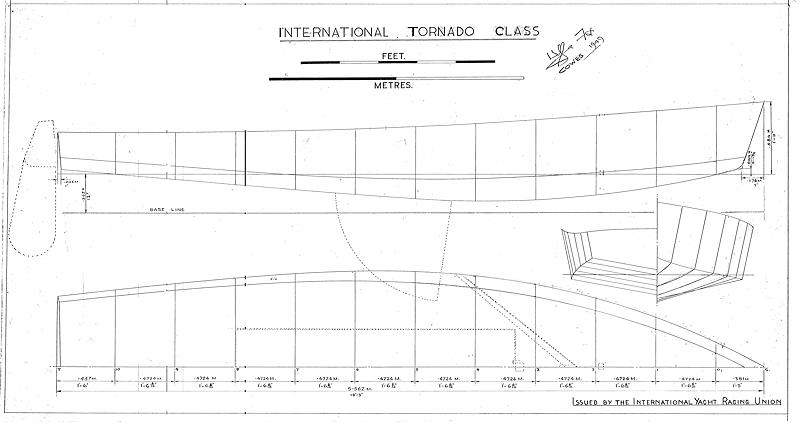

Worried that this proliferation of new dinghies would result in a fragmenting of the existing class structure, the IYRU tried to impose their own ideas of what constituted speed into a new design, the Tornado (the monohull, not the catamaran that would come later), the resulting design was anything BUT quick. Just how far the authorities had got this wrong could be seen when Yachts & Yachting journalist Jack Knights described the design process as akin to “asking a pacifist to design a rifle!”

In getting it so wrong, the very thing that had worried the IYRU in the first place now fuelled the development of a whole new genre of dinghies, full of exciting designs that were larger, lighter, carried more sail and were kept in balance by having the crew out on the trapeze.

Looking back at some of the boats that emerged around that time, such as the Osprey and the Flying Dutchman, they can now be seen as game-changers that delivered a genuine step function in the speed of sailing dinghies. During a set of unofficial Trials held in Chichester Harbour during the late autumn of 1952, another sailing journalist and top crew of the day, John Westell, (who would afterwards use his experiences to design first the Coronet, then the 5o5) would be amongst the very first crews to experience the sensation of being out on the wire, with the spinnaker up, in very strong winds.

Although not a writer given to expansive comments and cheap hyperbole, John would later talk in excited terms of the incredible speed that they had achieved. Outright speed was clearly a factor that he was keen to tap in to when he set out to design his own entry for what was by now being described as ‘the search for the ultimate performance dinghy’.

However, it would not be long before the outright speed factor would enter into the marketing and sales spiel for dinghies, as during an event at Cowes, the Royal Navy clocked on their radar a Fairey Jollyboat doing 13.4kt on a reach. This was the fastest speed recorded ‘on the day’ yet it led to the Jollyboat being called ‘the fastest dinghy in the world’. This was despite the fact that in the IYRU Trials the boat’s performance had been described as “disappointing”, with it proving to be little quicker than an Osprey. It was also slower than the Flying Dutchman and Coronet (which would develop into the 5o5) with the speed gap even more noticeable on the reaching and offwind legs.

Over the next few years the Flying Dutchman, 505 and International Canoe would, on paper, all have to share this accolade as in the early versions of the Portsmouth Yardstick system, all three shared the same handicap number of 70, a couple of points clear of the chasing pack which included the Osprey and Fairey Jollyboat. The International 14, which until now had been the de facto benchmark of performance sailing, trailed along a further couple of points back. This relegation from the top tier of dinghies did not sit well with the supporters of the 14, who were at pains to stress (often, it has to be said, quite aggressively) that ‘speed is not everything’.

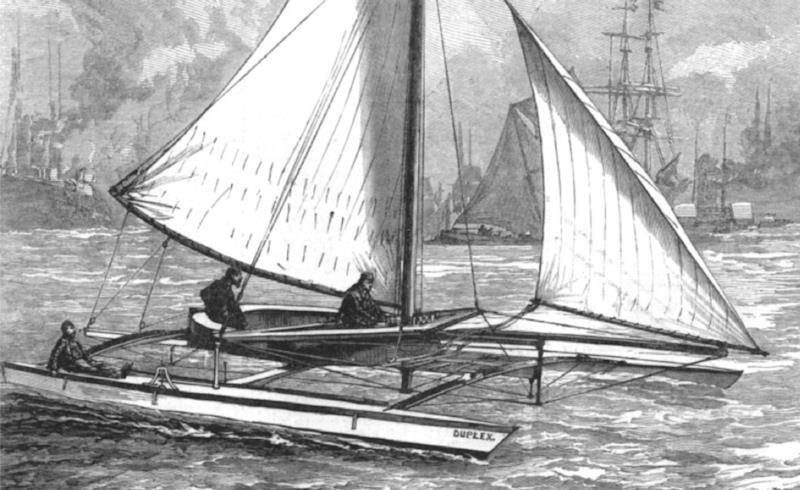

In this they would be proven wrong, for even as these leading edge dinghies were setting new standards for performance, in Essex on the east coast of the UK two brothers were carrying out some bizarre experiments that involved joining two canoes together with some bamboo poles. The basic concept of the catamaran was far from new, with multihulled craft being sailed by Polynesian sailors (amongst others) in amazing voyages across the Pacific. Nathaniel Herreshoff demonstrated a practical catamaran on the Thames in Victorian times, but in contrast to the heavy, deep keeled yachts of the day the performance difference was so great that many clubs banned further sailing in multihulls.

For Francis and Roland Prout, who had represented the UK as canoeists at the Olympics, those early experiments would result in their iconic Shearwater catamaran. Although there would be other cat classes appearing in the second half of the 1950s, of which the Jumpahead was probably the best known, it would be the Shearwater that gained the necessary traction to emerge not only as the dominant cat, but as the fastest thing afloat at the time.

With a 5o5 or FD sailing off a PY of 70, the early Shearwaters, with solid bridge decks, were already sailing off 65, yet this number was something of an average; on a breezy day and a reaching course, the Shearwater could sail well above its PY. If ever there was a speedy undermining of the 14s fallacy that speed wasn’t everything, then the rapid development of even faster cats made it clear that the pursuit of outright speed was now a mainstream occupation.

There were those however who wanted that ‘sizzle’ of speed but without the problems that seemed to go hand in with these first generation cats. The answer was to aim for multihull performance but from a monohull. In these pre-skiff days, the accepted wisdom was that to go faster you needed to go big or better still, go even bigger than that.

A decade earlier, when the IYRU had first been promoting the notion of performance sailing, the expectation had been for the very top boats in performance terms to have been sailed by a crew of three rather than the more conventional two. Their reasoning made sense, as with the technology that was available at the time, to take the next step towards multihull speed from a dinghy would require a major shift in the balance between hull weight and sail area.

If the very best in boat speed was the aim, the designers of the day recognised that in a hull form optimized for reaching, there could be advantages if they utilised a scow hull form rather than a more conventional dinghy shape. Rod Macalpine-Downie was already exploring the extremes of speed sailing with his advanced catamaran designs when he turned his attention to developing the ultimate in UK dinghy speed machines. His 24ft long Yachting World Scow carried 300ft of sail in the main and jib, plus another 300ft in the massive spinnaker.

This would all be kept in balance by a three man crew, the two forward hands out on a trapeze whilst the helm had a sliding seat (as the thinking was at that time that it would be too difficult to helm a dinghy from out on the wire). The designer certainly put a great deal of thought and innovation into this ‘super scow’ with twin centreboards and rudders that were both angled, so that when the boat was sailed heeled to reduce wetted surface area, the foils would be working at full efficiency.

Yet the YW Scow, and then Peter Milne’s attempt to make a monster version of his successful Fireball design with the Hurricane, would sadly prove to be almost classic ‘white elephants’. Although they were quick, increasing the hull size by 50% only generated a marginal increase in speed that was nowhere near that of the increasingly quick catamarans.

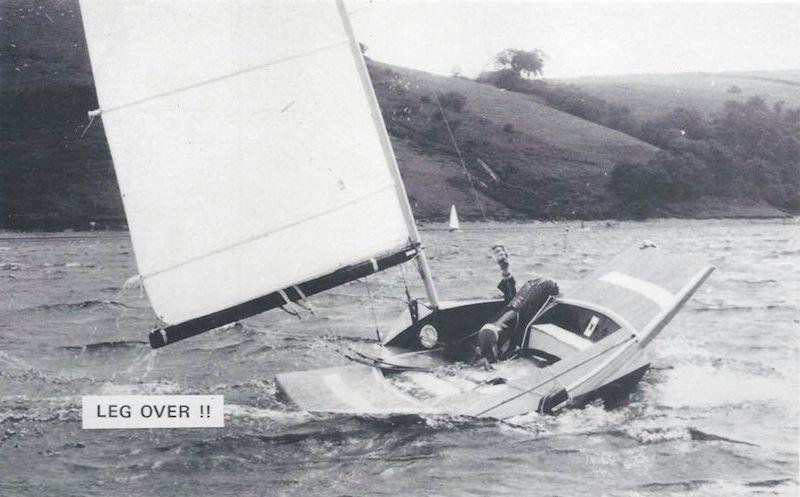

Moreover, the signs were that the International 14s may have been right; there was more to the sport than just going quickly, as this was soon seen to be highly relative to the sailing you were actually doing. Sailing one of the International Moths of the day, with its semi-circular hull form, may not have been that quick in breeze and waves, but the sensation of being ‘right on the very edge’ was like none other – not that it lasted long before (even when doing everything right) you still ended up blowing bubbles as you cursed the handling characteristics.

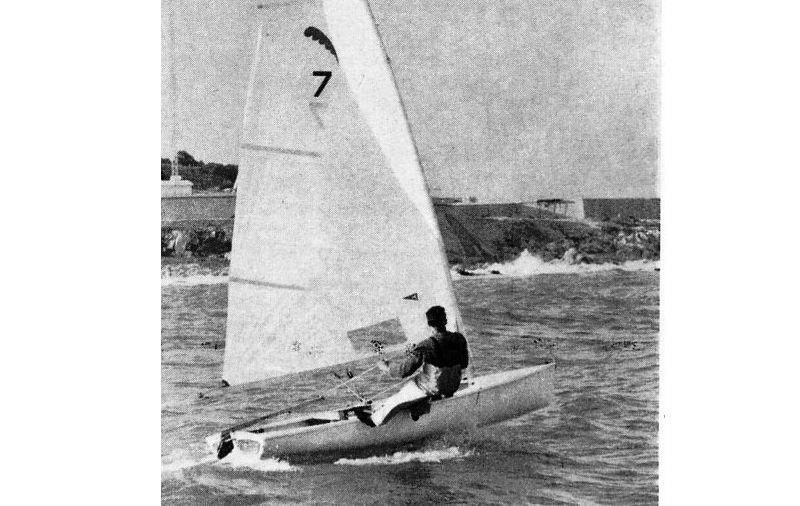

It would be the Moths found who would find that there was an ‘absolute’ in terms of that Greed for Speed, when they put in an entry to the 1965 IYRU Performance Single-hander Trials at Weymouth. As most of the boats there were 16ft long with close to 108ft of sail, the 11ft long Moths were at a huge disadvantage.

As Moth champion Chris Eyre, who was sailing his boat at the Trials, would say afterwards, “size does matter!” Yet those same Trials, then the following two iterations at La Baule and Medemblik that resulted in the Contender being selected, represented something of a break point in that search for outright boat speed, at least in the monohulls.

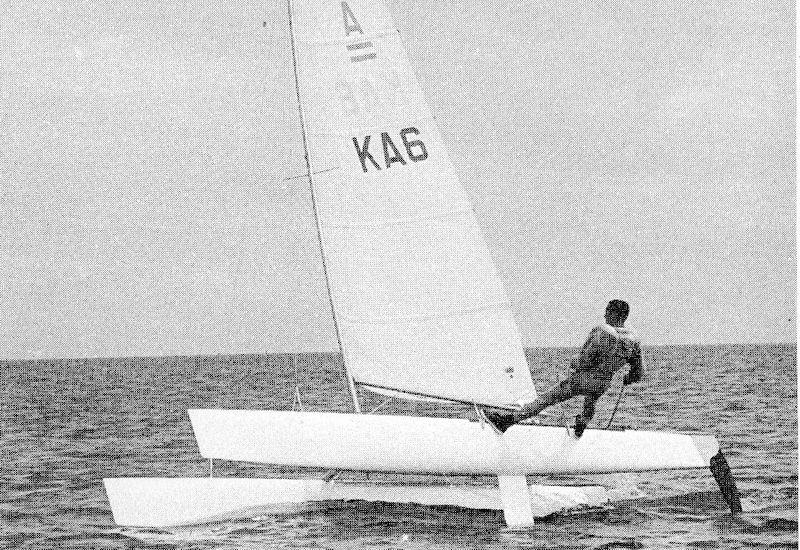

Meanwhile, the cat scene was going through a similar process that saw a double-headed set of Trials to choose both an international single-handed and two-man cat. In the same way that the Contender was a quantum leap ahead in speed when compared to the single-handers that had been around before the Trials, so the Australis and Tornado would raise the bar for cat sailing as they set new standards in the search for the ultimate in speed afloat.

Thankfully, that Greed for Speed would now stabilize on a plateau and though the relentless march of progress would continue, this was mainly taking place in terms of evolution, rather than revolution, and on a class-specific basis. In the one-design fleets, most helms knew which of the many options were best (see One Design or Two) which was great for the fleets, as everyone had pretty much the same kit to play with.

In some fleets, this level playing field became almost a testament of faith in the class, with boats such as the Solo offering fantastic close quarter competition right the way through a bumper-sized fleet. It didn’t matter that you were not sailing that fast, as everyone was going at the same speed.

At the same time, a sub-genre of the sport had developed that wasn’t even interested in the usual round-the-buoys racing, as the ‘speed freaks’ came up with ever more bizarre machines that were the ultimate in one-trick ponies, as all they did was sail over a short distance, in a straight line, but very, very quickly. Whilst the resulting annual Speed Week at Weymouth was all about serious technical innovation, it was also a lot of fun and without a doubt would provide a cross fertilization of ideas back into the mainstream of the sport. Developments that required more exotic materials and specialised fittings, that had previously been the preserve of the dedicated one-off, now started appearing in everyday surroundings.

Nor was it just the technology that was changing, as that Greed for Speed now started to encompass the sailors themselves. From the earliest days of sailing there had been those competitors who were part of the supply chain into the sport, the boatbuilders and sailmakers to the fore, but as winning became ever more the sole objective, the indistinct lines of status between amateur and professional increasingly became blurred.

The IYRU tried to stem this tide by trying to insist on strict Corinthian principles, but the battle had already been lost. The growing commercial pressures that had seen the ‘hired guns’ at the top of the Olympic and International fleets now saw ‘pro by any other name’ helms moving down into what might have been previously described as ‘recreational’ racing.

The majority of sailing was though still taking place in the boats that the so-called golden generation from the 1960s and 70s had made their own. To the Enterprises, GP14s, Solos and OKs would be added the Laser, a boat that had brought about the demise of so many splintered domestic classes, yet in just this handful of adult-centric classes, so much of our sailing was taking place with little reference to outright speed.

The advert for one of the leading sail lofts of the day declared, “boatspeed makes you a tactical genius,” yet any advantage was barely discernible. Instead, getting ahead took talent and a grinding determination to create an advantage on a boatlength by boatlength basis, all of which could be thrown away with one bad tack or missed wind shift.

This though was still the era when sailing had it all: it was accessible and with big fleets even at quite small events, there were enough people to make the whole thing fun, both afloat and ashore. This relative stability was about to get flattened by a revolutionary double squall as the skiffs swept in together with the next generation of SMODs. At that time, and since, there are widely differing views on how the SMODS have exerted such an influence on the dinghy scene.

On one hand they could be seen as the salvation of the sport, which would be all the poorer now without them. At the same time, the traditionalist viewpoint was that this was nothing more than a small number of people who had set out to make a large amount of money at the expense of the sport. Worse, the predictions from the naysayers spoke of an increase in the churning of new classes, to the point that in the end they would be cutting the throats of the boats that they had earlier launched onto the sport.

The point that they missed was that the SMOD backers were actually being very clever in the way they applied modern marketing theory to identify potential gaps in the existing range of dinghies that they could profitably exploit.

However, just creating a SMOD version of a boat such as the Merlin Rocket might have been risky (indeed, someone had tried it already), so it made sense to give any new design a step function forward in performance. So marked was this that the RS400 moved the hiking two person boat up to a point that it was now significantly faster that the trapeze-rigged Fireball.

In the same way the RS600 raised the performance bar from the Contender, which was at the time the benchmark boat for a performance singlehander, hoiking it up to something much closer to the speed of an International Canoe. Little wonder that a sailor who had form with both the Contender and the RS600 described the latter as, “a Contender on steroids.” That is a pretty good description, as the RS600 is an amazing boat that delivers a degree of outright speed that the older, heavier Contender simply could not match.

Yet at the same time, the sparkling performance of the 600, over and above that of the Contender, simply highlighted yet another great truism that applied to the path of dinghy development. Not just going fast but going a LOT faster would come at a cost. To be this quick boats had to be lighter and stronger and by the virtue of being more highly stressed, tended to break more often. Then there was that interesting question of how sailable a much quicker boat would be.

Nobody would say that the Contender is an easy boat to sail and not long after the class was launched in the very early 1970s, one competent single-handed sailor who had bought a boat tried to sue the builder for selling him a dinghy that was ‘impossible to sail’.

Yet by the standards of today, the Contender is considered fairly staid and placid, whilst the lighter, more powerful 600 will always be a tricky handful in wind and waves and is ever ready to ‘bite back’ at the unwary helm.

Over in the multihull world, that same sudden urge to go faster than fast was also bringing what some called progress, but what looked like a retrograde step to others. The wonderful Tornado, which had surely been the epitome of the ultimate in speed machines, was suddenly found to be lacking in ‘grunt’ so gained a second trapeze and a spinnaker for the downwind legs.

For many years the single-handed cat scene had been dominated by the Unicorn, which (once the rig had been sorted) became pretty much ‘the’ A Class Cat. Despite the light construction, healthy numbers and a strong class association helped develop the Unicorn into a robust performer, able to continue racing in all but the windiest of weathers.

More importantly, the John Mazzoti design could be built at home or finished from a kit and provided an accessible pathway into high speed sailing. Then the Greed for Speed took over, with a new breed of expensive high-tech A Class Cats that might have been significantly faster than a Unicorn, but at the same time were much harder to sail and suffered from a lower limit on the upper wind strength.

The speedy RS600 and the other skiffs that sprang up in those heady days of the skiff revolution might have thought that they had redefined the art of speed sailing (as they would be significantly faster than the massive YW Scows who were supposed to be the fastest thing on a single hull) but even their speed was about to be eclipsed by one of the smallest boats in the dinghy scene. The International Moths, which had previously only been able to offer the sensation of speed, now started to deliver the real thing.

A boat that at the start of the dinghy boom had been rated as slower than a Firefly, was now quicker than a Fireball, and when they started to overtake 505s on the water then people started to really take notice. Like a high jumper, this though was just their warm-up run as the Moths then lifted up onto foils and away into the history books.

For a while the Moths were all about the speed, until everyone in the fleet got themselves sorted out, at which point everyone was back going at the same speed again, albeit very quickly. In a class like the Solo, close quarter racing means just that – you’re close; at the speeds the Moths were now sailing at, being on the same square of an Admiralty chart was considered neck-and-neck.

Sadly though, boats like the Moths and the America’s Cup boats had somehow created a narrative that ‘foiling is the future’, with anything slower being a fast track out of the sport and into obsolescence. The final Dinghy Show at Alexandra Palace was littered with new foilers of all shapes and size, yet with little in the way of consideration being given as to who will sail these amazing machines and where. Even the Moths, at a mere 11ft long, still need space and open water to get airborne; anything bigger or quicker and you’re talking the larger bodies of water inland or out on the sea.

Much is also made of the incredible Who’s Who that make up the Moth fleet, and if recent world events are to be a measure of the talent in the class going forward, even the mid-fleet will still be packed with top helms from other classes. But all this speed and competition doesn’t come cheap and when sailors in other fleets talk of having invested in excess of £30,000 just to get all the kit that was required, it is clear that this Greed for Speed is doing little to make the sport accessible to all.

If the cost of getting a competitive foiling Moth was an issue, then the problems were only multiplied in the multihull fleets. Even with twin wires and a spinnaker, the Tornado still failed to tick enough boxes to keep its seat at the Olympic Classes table as it lost that slot to the Nacra 17.

Like the Unicorn, the Tornado had developed into a superb racing machine that could be pushed hard in most conditions, but the sensitive and tender Nacra required very careful handling, and even the cream of multihull sailors were soon picking up a level of injury that had scarcely been seen before. For a boat that was hardly seen outside of Olympic-related competition, the decision was then taken to apply the ‘foiling is the future’ philosophy to the Nacra, which was a boat that was already difficult to sail,

Expensive and requiring careful handling both ashore and afloat, the Nacra would be joined on the ‘barely accessible’ pedestal by the very latest of A Class Cats as these too were now foiling. The multihull Greed for Speed had reached an almost logical conclusion with a boat that was so much faster than the Unicorn, yet the older boat had been able to attract a broad base of participation, further proof (if any were needed) that following that path towards the ultimate in speed for a few will come at the expense of the ‘loss of the many’.

And still the marketeers who now seem to be the driving force behind our sport today are following their determined dogma that somehow the best interests of the sport will be served by accelerating the churn rate towards ever faster versions of boats that in the past had been ‘sailable by all’ and were now increasingly just the domain of the practised and fit few.

This mindset, that new boats should be for ‘the elite and not the lot’ is just one of the factors that is behind the increasingly worrying loss of critical mass of participation in the sport. Yet that headlong drive towards ever higher performance is taking place at a time when all the indications are of a strong statistical co-relation between performance (as expressed by PY number) and loss of numbers.

It has been said on this website so many times before, yet it is such a strong message that it pays to say it again. Dinghy sailing, first and foremost, should be about having fun and there would be few that would argue that going fast IS having fun. But you don’t have to foil to go fast, you can have just as amazing a ‘thrash’ in whatever you sail.

Single-hander or double-hander, the fun is on how you can sail your own boat fast, for speed, as we have seen, is all relative to what you do it in. Following that Greed for Speed may get you from A to B a bit quicker, but to what point, when there is so much more fun to be had going slower, often in nicer locations and with more company!

by David Henshall